At recent global health meetings that assessed progress made against the HIV epidemic, presentation after presentation confirmed that the world is inching closer to epidemic control. The excitement at these gatherings was palpable. It would be the first time in human history that such a public health milestone would be achieved without either a cure or a vaccine.

As technical experts attending these meetings, we were struck by the critical importance of logistical and operational interventions, alongside biomedical ones, to reach the last mile. Yet, unlike the private sector, public health systems in low- and middle-income countries often remain underfunded and understaffed. This environment can make project management very challenging.

The use of data to identify and reach populations most in need and then to link funding to specific targets presents operational challenges for ministries of health and nongovernmental organizations. FHI 360’s new management intervention, Total Quality Leadership and Accountability (TQLA), can make a significant difference. In the past two years, we have applied this novel approach to eight HIV projects in five countries and observed major improvements in the identification of people with HIV who did not know their status (new clients), initiation on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and retention in ART programs.

What is TQLA?

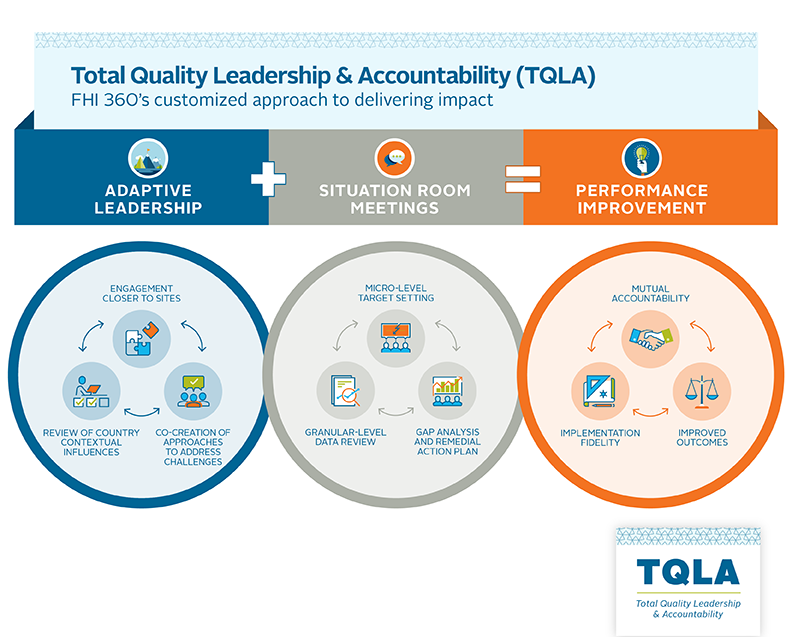

Our TQLA approach has three core elements: adaptive leadership, situation room meetings and performance improvement monitoring (see Figure 1). Together, they strengthen the capacity of program managers and health care workers to use data for planning, adopting local solutions to program weaknesses and requiring accountability. Individual health care facilities and their staff are allocated targets, such as identification of new clients, and are expected to report daily achievements against those targets, making decisions on resources in real time.

Figure 1

Adaptive leadership

In Zambia, we applied TQLA to the Open Doors project, a comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment program for vulnerable populations, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The team began by learning local issues that impact performance, analyzing data at a granular level and comparing each site’s performance against targets and deployed resources. It became rapidly apparent that low-volume sites received a similar amount of resources, such as funding or staff, as high-volume sites. As a result, the project leadership redirected resources to the high-volume sites, which were expected to identify and serve 80 percent of new cases. Concomitantly, if daily targets weren’t met at specific sites, the responsible teams were identified, actively engaged, immersed in their own data to identify root causes and mentored to improve.

Situation room meetings

As the second step of the TQLA approach, daily “situation room” meetings provide a way to evaluate site performance and then pivot resources and cascade accountability based on the results. Involving managers from the onset assures ownership and sustainability.

In Zambia, project staff met with local health facility leaders and other stakeholders to identify gaps, brainstorm solutions and prioritize areas of greatest need. This collaboration fostered an environment conducive to mutual accountability. At the daily close of business, sites submitted data on key indicators, such as the number of people tested, the number of those who tested positive and the number who started treatment. The data were then aggregated and visualized in charts. Staff discussed trends and made actionable course-correction recommendations. “Struggling” sites received tailored assistance, such as mentoring on the use of a new tool or role-playing for seeking consent to trace a partner of an HIV-positive client.

Monitoring performance improvement

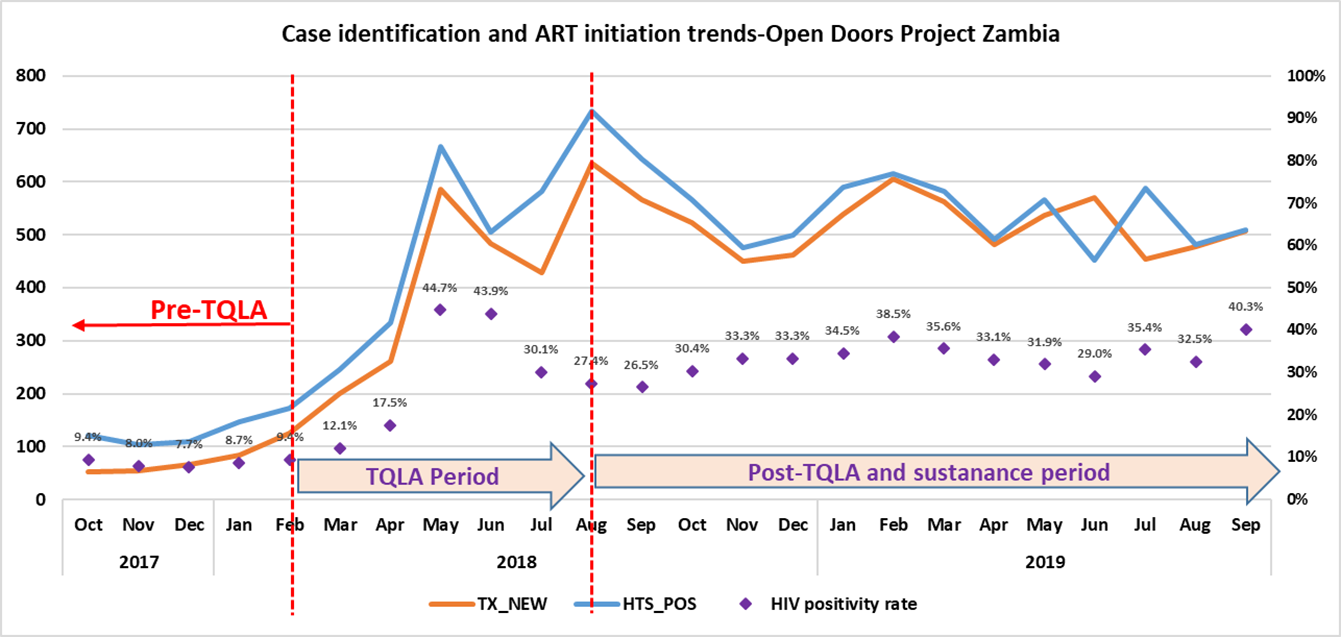

We observed a dramatic improvement in Open Door’s performance in the months following the TQLA intervention. Plotting trends and monitoring progress in the presence of all stakeholders was highly motivating to frontline health care workers. The number of new clients identified and initiated on ART increased from a monthly average of 150 pre-TQLA to 577 post-TQLA. That performance has been sustained for nearly two years at an average of 535 cases per month (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Additionally, more efficiencies were achieved as the project adopted the best practice of index partner testing (testing partners and family members for HIV and initiating treatment if needed). Because of the more targeted approach, project staff tested fewer people and saved more time and resources (e.g., test kits) while identifying more clients. The rates of HIV elicitation rose from less than 10 percent pre-TQLA to an average of 30 percent post-TQLA.

As we saw in Zambia, our TQLA approach uncovered and addressed inefficiencies and moved our projects from “business as usual” to results-focused programming. The same staff, in the same project, increased project performance more than threefold without any additional resources. Further, the use of daily data catalyzed accountability and spurred internal competition and motivation, resulting in enhanced performance.

As a management tool, TQLA has applications beyond the health sector. The three core elements – adaptive leadership, daily situation rooms meetings and monitoring performance improvement – can be applied across all development sectors to bring about stronger program results.